The Queer Reading of Booster Gold: Part I, Chapter 1

That boy can be read as explicitly bent from his inception and now I'm gonna talk about why.🏳️🌈

Introduction

I’ve been threatening promising to write this whole dissertation on various social media platforms for awhile.1 Partly because — shockingly — I’ve never seen anyone else actually sit down and do it. A lot of people have written a lot of meta in fandom (and occasionally in professional spaces) about Booster and Beetle as a queer ship — look, you only need a log to build a canoe, but those two have enough material you could recreate the Titanic from it — but I don’t think I’ve ever seen anyone sit down and write about Booster alone from that frame of reference.

Given he’s been around almost four decades now, I gotta say, I’m kind of surprised.

The following dissertation, essay, treatise, what-have-you will have a few different facets. One, necessarily, will be a look into some of the sociological factors of how and why Booster reads as distinctly queer despite it never being explicitly stated in text. Another will be looking at how Booster’s own actions, reactions and dialogue reinforce that view.

If you’ve followed me for awhile, you’ll know I tend to look at both Doylist and Watsonian perspectives especially about him, because he’s one of the best comic characters I’ve ever encountered to lend himself to being viewed through both those lenses. That’s not always the case, even with truly excellent comic characters; part of that being the requirement for a fairly cohesive, coherent, linear story, which many — even most — of them don’t have. (The majority of the JLI is a delightful exception to that rule, though, too.)

For the uninitiated, the Doylist read means the ‘real world’ perspective. In the case of Booster, it’s a look at the writing choices of various authors over the years, storyline choices, art choices and the broader sociology of the world and times, and how all of those contribute to the building (and sometimes shattering) of him as a narrative device. The Watsonian read, on the other hand, is more of an ‘in universe’ kind of perspective. That particular view looks at Booster as a character unto himself, which means asking questions and speculating on what might be going through his head at any given time, or how the events around him might influence him, all based on what he’s actually doing in any given story. And let’s face it, psychoanalyzing fictional characters via good, old-fashioned immersion is one of the great joys of devouring media.2

In cases of backstory conflicts — ie, actual retcons, not elaborations such as those which happened between 1986 and 1993 — I go with the earlier versions, though information from the later versions might be kept, provided it doesn’t conflict with said earlier version. There’s no doubt some argument to be had about whether Booster could even have a rock-solid backstory because of the nature of time travel, but for the purposes of this piece and our sanity, we’re not going to dive into that here. And even though he does have a considerably more coherent and linear storyline than most, there are still inconsistencies that crop up; how those are handled will again largely be with a preference for earlier works. Therefore, most of this reading will lean on Booster’s pre-Flashpoint history, though there will be mention and reference to later works, too.

Finally, if you don’t know me, you’ll see that there is a fair amount of ‘Death of the Author’3 involved in this, too. Especially given there’s a whole lot of ‘author’ involved in comics. The essential theory behind that is not a threat: Instead, ‘Death of the Author’ means that even though an author might pen a story, their intentions for a text only go so far; that the reader’s interpretation of the text can be every bit as valid as the author’s intention. According to Wikipedia:

"The Death of the Author" (French: La mort de l'auteur) is a 1967 essay by the French literary critic and theorist Roland Barthes (1915–1980). Barthes' essay argues against traditional literary criticism's practice of relying on the intentions and biography of an author to definitively explain the "ultimate meaning" of a text. Instead, the essay emphasizes the primacy of each individual reader's interpretation of the work over any "definitive" meaning intended by the author, a process in which subtle or unnoticed characteristics may be drawn out for new insight.

Despite fandom’s common modern misunderstanding, it doesn’t mean there’s no weight nor importance to be given to the author’s intent or background. In fact, I absolutely believe Dan Jurgens’ background contributed to a bunch of his creative decisions over time, and I’m certain that other authors following him were likewise. It only means that the author’s intent or biographical information should never be the exclusive factors in how one reads and interprets any given story or character; works don’t exist in a vacuum, after all. The moment something is released into the world, it’s subject to the influences of the world in turn.

(Though there are discussions to be had as to how much or little one can divorce artist and work, particularly when you’re getting into Gaiman or Rowling territory; still, while that’s not the discussion here, it’s only fair to acknowledge that it is a legitimate one.)

Especially in a case like this one — the reading of a character as queer, and who comes across as even more queer the more closely you look at him and as time goes on — you can see where pointing out the subtleties and unnoticed characteristics might just make or break the premise, and also where the original intentions of the author(s) don’t necessarily matter more than the interpretation of the reader(s). We write the stories we want to read, but we also look for ourselves in stories written by others; it’s in this push-and-pull dynamic that you find the true beauty and meaning in storytelling.

And I think in the case of Booster, it more than just makes the premise.

I think it drags it right out into the spotlight.

Chapter 1: Time Traveling Back to 1986

Given the ultimate projected length of this document — whatever you might call it — I’ve made the decision to break it up into sections, rather than publishing it as one large, unbroken piece. So, in this first chapter, we’re going to go back to 1986 and work our way forward through time (much like our title hero) and examine different facets along the way.

Still, there will be mention of later works, and in all cases, I’ve endeavored to include (homebrew-styled) footnotes for quick and easy reference.

So, let’s get right into two of the most critical elements underpinning Booster’s entire early story.

Isolation and Exploitation

One of the most interesting facets of Booster’s story is that he looks more queer in retrospect, not less, and this can partially be attributed to the reality of what our world was doing at his inception and how his in-universe backstory intersects with it; further, how the evolution of his in-universe backstory over time offers a particularly poignant window into what the actual queer experience is like for many people even today, especially as you get into the parallel elements of the isolation and exploitation inherent in both.

Reading Booster as queer starts with the nebulous but critical ability to stand in his fictional boots, which is why the following is largely a Watsonian interpretation and does indeed require an understanding of Death of the Author.

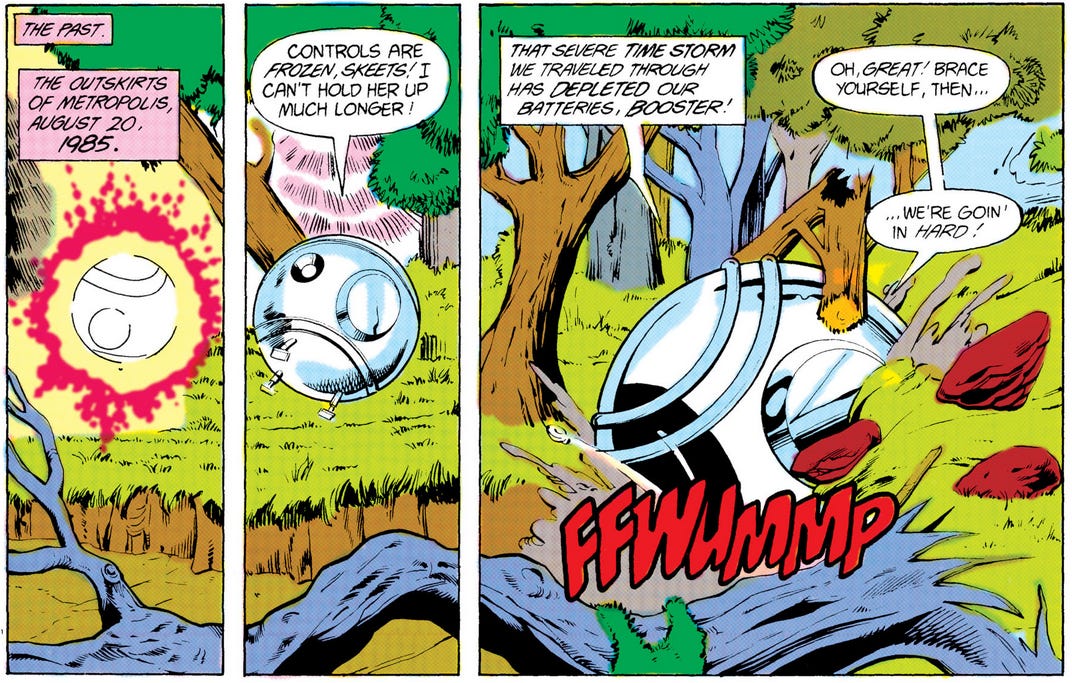

I discuss these elements at some great length in my review of Booster Gold Vol. 1, Issue 34 here on Boldly Reading, but in brief: Booster’s entire early story, both in his time and after he travels to the past, is one long and often wrenching tale of exploitation, at least until he joins the JLI. No matter what angle from which you look at it, he was a really young guy — either a teenager or just past being, depending on whether you follow actual canon dates or word of god — who was at the mercy of powerful forces well beyond him, and even those times it looked like he’d somehow asserted control over his life turned out to be an illusion.

I’m not going to recap my entire discussion here when you can just read it where I linked, but I will recap some of it to give real context on why I say his story echoes the queer experience, starting with his isolation and continuing on into how exploited he really was.

Just in his own time, before ever coming back to August 20th of 1985, the factors adding up against young Michael were:

An abusive, criminal father who beat his mother so badly she ended up hospitalized repeatedly, before ditching the family, leaving them destitute.5

Growing up in grinding poverty in a world where neither housing nor healthcare were a guaranteed human right, and where a person’s very life was at the mercy of capitalism, as well as the chronic, inescapable stress that can cause.67

Living in a world where organized crime syndicates were powerful enough to control a great deal of the flow of money and influence. (The Rubenicos controlled half the Eastern Seaboard, Booster says; it might not be hyperbole, either.)8

This isn’t necessarily at odds with Rip Hunter’s description of the 25th Century as, “America recovering from nuclear war, her cities full of fear and despair, a ruthless police state,” either.9 All you have to do is look at our world today, as of 2025, to see exactly how such a thing can play out.

A world where ostensible good-guys and acknowledged bad-guys alike gamble astronomical sums based on the skills of one college quarterback, and their ability to manipulate him. Or punish him. Or both.10

The factual financial exploitation of college athletes can be assumed to apply in the 25th Century, given how many other sociological factors parallel the modern day.11 Likewise with the rate of injury for college football, which is reflective of how young men use and abuse their bodies for a shot at something better.12

The pressure at home to do something, and to do it quickly, because his and Michelle’s mother isn’t going to survive much longer and Michelle’s already at the end of her rope.13

Even before Dan added Booster’s deadbeat father into the mix as a factor in Booster’s fall from grace in far-later iterations of his backstory (which I generally choose to ignore for academic purposes as it conflicts with Booster’s original backstory), he was already in an impossible situation. There can be little doubt that if he hadn’t played ball — literally or figuratively — there was an implied and legitimate threat to his life and the lives of his immediate family.

Additionally, here are some things we never see nor hear mention of:

Any friends or extended family Booster can turn to for emotional support, let alone financial help; his isolation is even more crystalline in retrospect, too.

Any evidence that he had any resources whatsoever that he could pull from, aside his own body and what he could do with it. (There’s a not-insignificant correlation proposed between the plights of amateur athletes and laborers and those of sex workers, in terms of lack of both options and agency.14) He borrows money from the mob in order to make the money to save his mother and pay the mob back and, in a position with no leverage whatsoever, ends up blackmailed for it.15

Any evidence that the police or any other authority would offer him a legitimate way out: In fact, later, we see them offer to help him only to screw him over. (ACAB, kids, apparently now and always!)16 And never mind Broderick literally gunning to execute him without trial when he returns to the future; in fact, practically salivating over the idea.17

It's in the metatextual that this particular aspect of Booster's backstory — the layers of both isolation and exploitation, the effects chronic stress would have on an adolescent/young adult (and his willingness — and unwillingness — to take risks18), a hostile sociological environment, a distinct lack of protective factors — echoes the queer experience; later, there’s much more direct evidence, openings you can drive whole trucks through, but even back here, this dog is already definitely hunting from the outset.

Standing alone, it might not make a premise, but taken in the greater context, it only enhances what comes later.

Because it's not just in our own distant past that queer kids live the cruel reality of being so alone and vulnerable; in this modern world, today, LGBTQ+ kids often suffer that exact same isolation and marginalization as they have historically, under active threat of harm and with no where to turn to and no way out. If they aren’t treated as political footballs by society, then they might still suffer for their queerness at home, and all too often, they have little more than their own bodies and what they can do with them to survive by19. Our political reality now just brings it even more into line with the fictional cruelty of the mid-25th Century, for that matter.

Turn any which way in the queer community today and you’ll find some kid backed up against the wall, and a whole community — or nation — ready and willing to use them or abuse them or both—

—and you’ll often find that same kid making desperate, oft-naïve, and sometimes really bad decisions to escape that impossible pressure, too.

Sounds familiar, doesn’t it?

Still, if this was the only evidence for Booster reading as queer, the hound would lose the scent. Isolation and exploitation alone do not a queer reading make, even if they're a compelling example of circumstantial evidence.

So, let's move onto the next thing, which is much more damning: How the boy himself acts.

Masking (and Closeting) in Plain Sight

The Unreliable Narrator

One of the most fascinating things about Booster, as a character (Doylist) and as a person (Watsonian), is that in either form, he’s the quintessential unreliable narrator.20 Before you even get into dissecting his in-universe choices, and how those read in the real world, before you start to analyze Dan Jurgens and his writing decisions, you have to acknowledge that Booster’s an unreliable narrator, as it’s actually a decent piece of evidence as to why the queer reading of him is both easy and legitimate.

For a little information: Unreliable narrators aren’t always just liars, though they can be. They can also be working from a place of imperfect understanding. They could be mentally ill. They could be missing parts of the story without even realizing they are. (They could be all of the above.)

Unreliable narrators also aren’t necessarily lying out of any kind of malice. I suppose a good way to explain it quickly is: The unreliable narrator is very subjective, rather than objective, at least enough that their credibility is immediately suspect. You can’t exactly trust, with an unreliable narrator, that you’re getting the full and accurate story. As a reader, you have to decide how much weight to give the narrator’s interpretation of events and often you have to seek more information than your narrator might give you in order to achieve some more objective understanding.

Booster, in canon, willfully lies more than once in his first book, and often without so much as a hesitation. And when he’s not lying overtly, then he’s likewise capable of lying by omission just as easily, which is such a fundamental part of his character that it takes all the way from 1986 to 1993 to assemble what one can assume is the most complete and accurate take on his biographical backstory, though we do come closest to a full accounting in ‘89. While there seems to be little to no actual malice behind it — in fact, he mostly seems to lie in self-defense — there’s no denying that he’s doing it intentionally.

The other part of this, though, is that Booster’s credibility as a narrator isn’t shot just because he lies — overtly or covertly — with intention.

It’s that sometimes, clearly, he doesn’t intend to be dishonest. That his view and interpretation of events is just so skewed out of true that you have to ask more questions, because whatever’s going on in his head, it’s openly defying what one could argue actually is an objective and observable reality.

A good illustration of this is how he tells his backstory to different people over time and what stays the same about it: Even when he’s giving legitimate reasons why he would resort to gambling and game-throwing — because his family is destitute, to save his mother — he’s consistently and unhesitatingly blaming himself for his own downfall without trying to pin that blame on someone else.

Even when he finally admits to being blackmailed into throwing games, it isn’t apparently — in Booster’s mind — enough to absolve him of an unfair level of responsibility for what is such a clear, concise and chilling example of exploitation. We’ve already established the list of what resources Michael had to fall back on, outside of himself, which was— well, none.

Even when he’s able to acknowledge he’s in a no-win situation, even after he recounts how he was blackmailed, he still pivots right back to how he got greedy and makes it clear how it was ultimately his own fault, how he ended up.

The single shot he takes at really sharing the blame is in Justice League Quarterly #10.1, but even then, he doesn’t quite make it out from under it.

It’s in Booster’s evolving backstory that you’ll find the best examples of him being an unreliable narrator, both in his lying by omission and in his fairly merciless view of himself. Whatever drove Dan’s decisions in adding to and parceling Booster’s backstory out over time in that way, the result of said parceling — particularly viewed in retrospect — is both brilliant from a storytelling perspective and deeply fascinating from a psychological one.

Rather than reading as Jurgens not knowing what he was doing, it instead reads like he had a long game he played with his creation and that he was explicitly writing from the jump with that in mind. Regardless of whether he did or didn’t, though, the result (beyond brilliance in storytelling) is a character who regularly comes across, to use an internet-ism, as a tall stack of trauma issues, masking behaviors and ultimately closeting behaviors, hiding in a trenchcoat.

And it’s also a significant contributor to Booster looking more and more queer as time wears on. Because once you allow for the demonstrable fact that Booster is a highly unreliable narrator — both in the sense of his ability and willingness to lie intentionally and in the sense that his perspectives are skewed out of true — suddenly a handful of flirtations across forty years of history and some bragging starts looking a lot less like explicit heterosexuality and a lot more like a man in a closet.

Especially given every single other piece of evidence, most of which we still have yet to explore.

Masking Behaviors

Much is made about how Booster wears his identity publicly and doesn’t have a secret identity, which is technically legally true (he’s legally Booster Gold in costume or out)21, but is literally very untrue (he’s actually Michael Carter). Moreover, though, he’s a master of hiding his authentic self from the world and does such an incredibly good job of it that those rare times he drops that mask and shows who he actually is under it drive that point home sharply. And he only does that very selectively over the years, too.

By the time you reach the end of the pre-Flashpoint universe, there are only two beings we actually know of who really seem to have gotten a look at Booster as a whole person in a very unguarded state with any actual consistency: Skeets, of course, and also Ted Kord, the second Blue Beetle.

No small part of why Booster reads as queer even in Vol. 1 originates in this style of masking. Partly because it is masking, which is something that most queer people have to do in their lives at some point or another, and partly because of how Booster specifically goes about it.

For the uninitiated, according to the comprehensive definition on Wikipedia22—

In psychology and sociology, masking, also known as social camouflaging, is a defensive behavior in which an individual conceals their natural personality or behavior in response to social pressure, abuse, or harassment.

—with an emphasis on how masking can relate to not only closeting (which is a type of masking and a distinctly LGBTQ+ term) but also to trauma. And to look at Booster as closeted, you also have to take into consideration the psychology of masking trauma, too, because these fundamentally play off of one another and the ability to do one often informs the ability — and inclination! — to do the other. So, for a quick list of things Booster very much keeps to himself and hides (or lies about) as a matter of either instinct or self-defense, at least until he’s either given no other choice or until he trusts someone enough to tell them:

His actual given name. Skeets knows it and reveals it to Superman in Booster Gold (1986) #6, but it’s not until Issue #10 that Booster tells anyone his name himself, and that’s only Trixie. (She then proceeds to use it as something of a leash throughout the rest of the book, which might explain why he doesn’t give it to anyone else for quite awhile after.)

As an aside, though: Despite fannish meta, there’s no evidence that Booster actually gets offended or has any issue whatsoever going by Michael, only that he’s really selective about who he even shares that name with in the first place. That he seemingly views it as something intimate or vulnerable and thus hides it, which suggests that when he does give it, he might very well expect that offered vulnerability — and authenticity — to be treated with respect and not used against him. The second present-era person we know of for certain to have been given it willingly, after Trixie, is Ted2324, who tellingly does not really use Booster’s given name casually. (Whether you consider Giffen’s and DeMatteis’s retcon of Dinah both knowing it and using it25 later as legitimate is up to you, but it doesn’t really fit earlier stories, so I’m inclined to ignore it. Same with their retcon of Ted doing so in ‘future history’; it doesn’t fit anything established earlier.)

When Ted does use Michael — rarely — it’s almost always with some narrative weight behind it. It’s an attention-getter for both the reader and Booster himself because of that.

Of course, once it becomes common knowledge many years down the road, everyone and their metaphorical or literal brother starts calling Booster by Michael. He doesn’t seem to take exception to it outwardly, despite the fact that it does occasionally still seem to be used as a leash or in an attempt to force intimacy where he might not be inclined to give it, but we can’t really know how he feels about it, as he never says anything or reacts one way or the other. Either way, he’s not precious about his name, but he does clearly, canonically guard it, at least up until it’s a lost cause.More than many things in these early stories, this specific kind of masking that Booster does here — of identity — is an incredibly powerful allegory to closeting, and a likewise powerful contributor to him reading as queer. And while it might be most strongly represented by the way he guards his given name, it permeates the entirety of his first volume in several ways beyond that.

The mere existence of his family. When Dirk and Trixie show up to wake him up in Issue 5 — which is some very unsettling boundary-violating by them both, frankly — and Trixie gets curious about the holo of his sister and mother, Booster reacts sharply and grabs it back and snaps at her to put it down. And not unreasonably! Not only did they essentially come into his bedroom uninvited while he’s asleep, but getting into his personal possessions right on the heels of it is an additional boundary violation, however mild and/or innocent it’s portrayed as. (And tellingly for Booster’s innate nature, he apologizes immediately for snapping, even though he’s not actually in the wrong there. He had every right to push back. It also says something about how poor his own boundaries are that he doesn’t enforce them even more strongly in this scene, because while it’s portrayed narratively as somehow okay, most people would agree that it’s actually really and emphatically not. ) Regardless, he doesn’t explain or offer them any information until later, as stated in point 3 below.

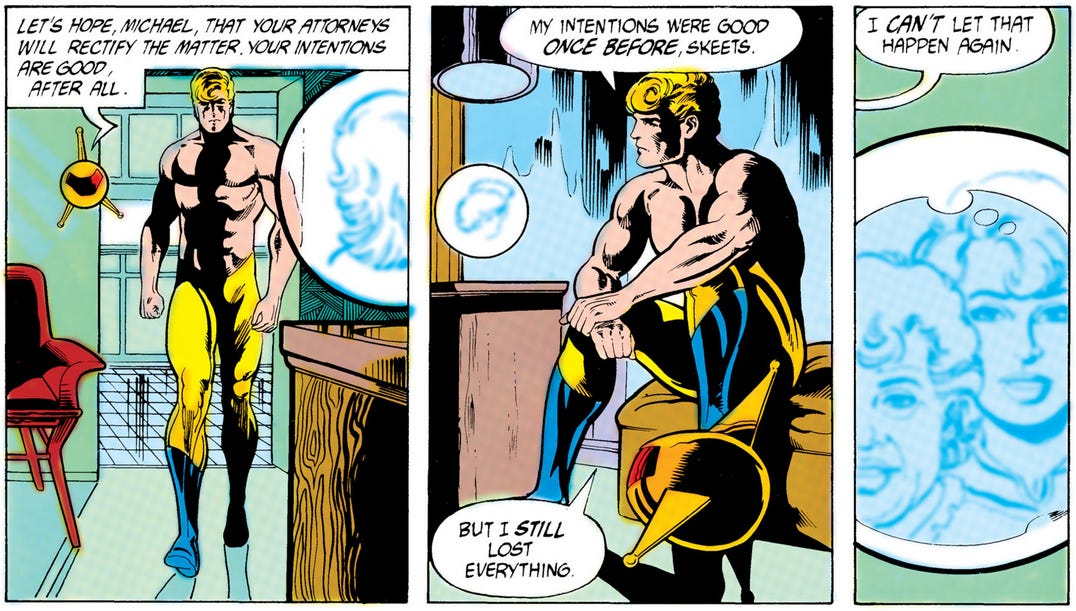

Why he did what he did, in the 25th Century. In Issue 5, he brings up to Skeets — who clearly already knows the story — that he was trying to do good when he was throwing games and that he lost everything for it. This is something he doesn’t tell anyone else until much, much later, though. He talks about how poor his family was in his first volume, but only right when his comrades are about to see it for themselves. It’s not an offered opening, it’s literally just a biographical confession; even Booster says he’s ‘coming clean’26. There can be little doubt he would have continued to keep his mouth shut about it if his hand hadn’t been forced.

The first time we ever see Booster voluntarily talk about his mother’s illness — and therefore his impetus to start gambling — is to Ted Kord, a few years later.27 (And again, this is also the only time Booster ever tells anyone he was being blackmailed by the mob. In nearly forty years.) Notably, this issue has Mark Waid as editor, who will later himself revisit Booster’s backstory in 1993 and therefore knows about the blackmailed-by-the-mob part, but chose not to include it in the ‘93 story despite it being very, very heavily implied as having happened in the text.28 There’s a whole dissertation all by itself, what that kind of omission, paired with nightmares, says about Booster’s mind-state and self-view in-universe.

Further — and this is also very telling — Waid makes it clear that Booster hasn’t told Fire, Ice or Guy that story in any form at all. By that point, given the length of Booster’s hair and other context clues (Ice being present but Guy having Sinestro’s ring), they had been teammates for a number of years. But only Ted seems to have been given that story by then.

How lonely Booster feels. Trixie half-senses it, but only Skeets really gets to hear the full measure of it from Booster himself.

Arguably, his age. He says he’s (at least) twenty-two, except when he’s accidentally admitting that he isn’t29. But the dates very consistently say he’s 19 in 1985 and therefore likely 20 when his book starts.30 Further, Skeets suggests he’s supposed to act like he was born in 1966 as of either ‘85 or ‘8631, which again, definitely makes him younger than twenty-two.

This adds some really awesome characterization to Booster, though: Lying (in this case certainly a type of masking) to make himself appear older, for one — because that would heavily imply that he’s aware no one’s going to take a brand new, solo teenaged hero seriously (and also that being a couple/few years older might hold at bay more predatory elements from the outside) — but also the fact that he would have still been just barely an adult when the worst of his blackmailing/game-throwing/disgracing went down in the first place. The toll that had to take on him mentally neatly explains why he would steal an armload of gear and bolt into the past seemingly halfway on a whim.

Just for further context, Dick Grayson is established as 19 in New Teen Titans in 198332. However you hash it, Booster’s absolutely Titans age, which is relevant to points which will come up later.

How he actually feels about things, emotionally speaking, though that can be contingent on the level of vulnerability involved and the era. He’s conditionally more open as he inches towards middle age, but even then, he’s not exactly good about it. He’ll admit he’s frightened when he’s literally blind and at the mercy of whatever Jack Soo can do to restore his sight33, but throughout most of Volume 1 (and indeed throughout the rest of his publishing existence), Booster has a very real tendency to conceal what’s going on with him internally from nearly everyone else. The exceptions consistently being — again — Skeets and Ted; the first is his primary confidant in Volumes 1 & 2, and the second is the same from Justice League International onwards. (And emotional outbursts, while revealing, aren’t the same thing as openly, willingly communicating something vulnerable to someone else.)

Even with his own twin sister, he stays guarded until she’s ready to walk out on him; only then does he scramble to get emotionally honest with her, and it certainly doesn’t become a habit afterwards.34His physical state, when he’s been wounded. Booster doesn’t really complain overly much about being beat up; when he does complain at all, it’s usually because it’s something mild, which he’ll gripe lightly about. But when it’s serious, he’s far more apt to conceal it; even when he can’t conceal it, he doesn’t say much about it and seemingly prefers to try to power through it sans any attention.

The best example for this is in Extreme Justice, where he’s suffering no small amount but chooses to actively hide it even from Ted35, but that’s hardly the only example. He also supposedly gets out of being beaten by Doomsday unscathed36, but given the state of his powersuit and the fact that he got his head slammed in a car door after being beaten to within an inch of his life (Guy reflects that he can hear the bones breaking)37, it’s much more likely (Watsonian) that he just kept his mouth shut about his own physical state, let people assume what they would and otherwise overlook him, particularly given that Superman was dead and his best friend was comatose. Years later, he takes a lightning bolt and explosion face-on, gets burned badly enough that medical professionals are surprised he’s able to breathe on his own, but still tries to get up to follow Ted, only to black out before he can make it two steps38; even then, within a couple of days, he’s leaving the hospital and once again doesn’t so much as whisper a complaint about any pain, despite still wearing the bandages39. Shortly thereafter, his vambraces and gauntlet blasters basically get melted to his forearms and his response is to try to go back and fight regardless40. Then, some sixteen months after that, he again gets beaten half to death, this time by the Joker, and suffers it without complaint; indeed, in the desperate pursuit of saving Ted, he’s ready to keep trying regardless.41 And a few years after that, Maxwell Lord beats him to the ground with a chunk of concrete at the end of a piece of rebar, to the point he can’t even sit up on his own42, and— well, you get the point. And those are just some of the big ones.

The reason this is so telling and falls under Masking is because, for someone who’s considered an attention-seeker by reputation, Booster not only consistently bypasses an almost guaranteed sympathetic source of it, he seems to actively avoid it as much as possible.

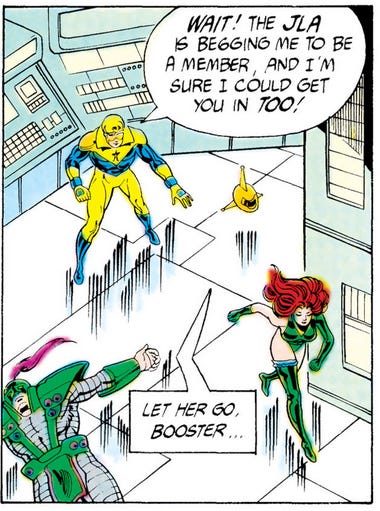

The act of masking — and closeting — one’s authentic self as a survival mechanism is immediately relatable to many intersectional groups, from those who are neurodivergent to those who are queer. Fundamentally, it contributes strongly to reading Booster as queer, as there’s no denying whatsoever that he’ll not only conceal quite a few things — including something as seemingly innocent as his own given name — but (bringing this back to him being an unreliable narrator) when the situation calls for it, outright lie. One example is his very passive-aggressive ‘date’ with Monica Lake, where he claims his powers are innate43 — we’re going to get more into that later, too — but another example is where he lies, inside the first handful of issues, and claims that the Justice League’s already basically offering him a spot on the team44.

Speaking of the somewhat mercenary Monica Lake, though, brings us to yet another very damning piece of evidence: Booster’s fairly obvious lack of actual romantic interest in— well, pretty much any woman.

A ‘Confirmed Bachelor’

Definitions of Queerness

For the younger amongst you, the term ‘confirmed bachelor’ was a type of coding in older generations, a way to say without saying that a man was gay. (Another coded, related phrase was ‘he never married’.)45 Both of them have become a little archaic, but they would have certainly still been in use back when Booster was fresh to the 20th Century, if towards the end of them being in more common rotation.

For the older amongst you, however, the more modern terms describing sexuality and romance might seem like a lot to take in. (I’ve been told this before by people relatively contemporary to me in age.) So, in order to give those of you who need it a quick primer — those who don’t can keep scrolling — the essential premise is that the following components of human attraction often fall under what’s commonly referred to as sexual orientation:

Sexual attraction46, which is not really on a binary scale. Rather, it’s more of a scatter graph; some people feel sexual attraction to others. Some don’t. Some feel it only conditionally. Of those who do, some might find themselves drawn more towards male-presenting people or female-presenting people — or neither! — or maybe they’re drawn towards a person’s personality regardless of perceived gender or lack of.

Asexuality refers to a (conditional) lack of sexual attraction. It’s a term unto itself, but it also acts as an umbrella to others. (Protip: Asexuality and sub-cartegories also absolutely fall under the firmament of queerness, too. If you’re ace, you’re one of us.) For the purposes of this dissertation, though, the main sub-categories that are going to come up are:

Demisexuality: The conditional sexual attraction to someone based on an established emotional bond.

Gray asexuality: Somewhere between asexual and allosexual, typically used to mean limited interest in sex, less than what would be considered the ‘norm’ for a given culture, but more than ‘none at all’.

Allosexuality, on the other hand, refers to the presence of sexual attraction. Namely, what the modern era (and the 80s) would consider the ‘default’. Of the allosexual terms that are going to come up:

Heterosexual (the other unfortunate ‘default’), the attraction to the ostensibly opposite sex.

Homosexual, which is the attraction to the same sex.

Bisexual, which is a somewhat binary term, but one still in use, referring to an attraction to male or female-presenting people on something of a continuum.

Pansexual, which is most often defined as sexual attraction completely regardless of and divorced from gender.

Romantic attraction is considered its own separate thing. While often interrelated, and sometimes used interchangeably, a person’s romantic inclinations aren’t always going to have much — or anything! — to do with their sexual attractions or lack of. And of those terms, you also have sub-terms, to include:

Aromantic, commonly considered a lack of romantic attraction towards others. You can be aromantic but allosexual in some variation. Or you could be aro-ace, which by now should be an obvious term. All of the same prefixes you see above in reference to sexuality also apply to romantic attraction, so I won’t rehash them. Demiromantic is one that will come up.

Alloromantic, which is the presence of the potential for romantic attraction. Considered the ‘default’. Same thing, too: all the same prefixes as allosexual with largely the same meanings.

Beyond that, there’s also an interesting sort of side category describing a type of relationship: Queerplatonic47, which is a deep, committed, queer-in-some-fashion relationship with many of the markers of what one would consider romance, but no actual romantic intention. Which will almost certainly come up in the next part of this dissertation/essay/what-have-you, so it pays to define it now for the uninitiated.

These various terms allow for a number of combinations to describe someone’s orientation and a facet of their identity; further, orientation throughout one’s life can change. Just as many children hate broccoli while young and love it as adults, people can be humming along thinking they’re hetero only to find out that they might just be a little bent themselves.

There are, however, some studies out there which can shed some further light on the subject, albeit taken with a grain of salt.

Applied Statistics

While there’s a solid argument to be made for Booster being somewhere more towards the middle of the Kinsey Scale48, he still remains firmly a ‘confirmed bachelor,’ essentially, until he dates Lorraine Reilly in the late 90s49. (Tellingly, he doesn’t marry her, either. Most in-canon references we do get about that relationship are really just about how stormy it is, though amusingly, the tabloid media does compare her to Ted50.) The one woman he allegedly did marry — as a contemporary character, not as a speculative future variation of himself — was the wealthy heiress Gladys51, but if you don’t subscribe to that being retconned52, (that is, if you even consider it canon to begin with53), then it’s still openly and admittedly transactional, at least on Booster’s part.

According to the exceptionally thorough research of Alfred Kinsey himself54:

Since only 50 per cent of the population is exclusively heterosexual throughout its adult life, and since only 4 percent of the population is exclusively homosexual throughout its life, it appears that nearly half (46%) of the population engages in both heterosexual and homosexual activities, or reacts to persons of both sexes, in the course of their adult lives.

If we’re to go by the Kinsey Reports — and Kinsey’s raw data, wherein “the sociological data underlying the analysis and conclusions found in Sexual Behavior in the Human Male was collected from approximately 5,300 men over a fifteen-year period,”55 — then the odds on Booster being at least some form of queer are roughly one in two.

A literal coin-toss.

Allow me to briefly step outside of the academic tone of this dissertation/essay/what-have-you to ask an important question:

Does anyone really think this man is not at least some form of bent? Anyone? Bueller?56

Anyway, to return to our prior tone: Even if we go with the number 37%, which is representative of Kinsey’s tally of men who had at least one homosexual experience — a number also essentially confirmed by Paul Gebhard, who (upon criticism of Kinsey’s statistics) stripped out the data that was alleged to create a sample bias — that’s still a better than one in three chance.

Various studies over time have purported to disprove Kinsey’s statistics, claiming everything from sample bias on Kinsey’s part to the disparity versus later studies. Truthfully, no two studies on sexual preference are the same; in one study from Germany, 18% of boys (nearly one in five) ages sixteen to seventeen in 1970 reported at least one homosexual experience. The same essential study, in 1990, returned an answer of only 2%. Considering the state of the world by 1990, there are several things you could point to in order to explain the disparity.

Regardless, one thing is in Kinsey’s favor: He made it a point to build a rapport with his interviewees and to train those under him to do the same, building trust, and therefore eliciting more frank and honest answers than anyone might have been inclined to give in the 40s otherwise.

Bringing this back around to Booster: a distinct lack of relationships in canon with female-identified persons, as well as considerably fewer markers of attraction, combined with the statistical odds of queerness in the 20th Century (let alone what they might be in the 25th Century), certainly point towards him being something other than the presumed ‘default’ of heterosexual.

When it comes to the burden of proof and preponderance of evidence, there’s surprisingly little of it one can point to in order to (attempt to) claim Booster’s exclusively heterosexual and a similarly minuscule amount of it one could use to attempt to prove he isn’t queer.

And part of this is how he tends to react to the women he’s surrounded by.

The Ace and Bachelorettes #1-3.5

There’s no real way to detangle Booster’s first volume from the latent sexism of his creator, which will necessitate a dive into the Doylist side of things later within Part 1. Somehow, though, despite the issues with Dan Jurgens and his portrayal of women in Vol. 1 (and indeed everywhere), Booster mostly avoids coming across as sexist himself throughout the book, and partly because he doesn’t actually come across as all that ragingly heterosexual. (And the worst one can really accuse him of, in terms of sexism, is being a little too free with the pet names as time wears on, and maybe a little too assured of his own desirability, which comes across as kind of silly and arrogant when viewed through a modern lens; still, back in those days, that sort of behavior was the background radiation everyone happened to bake in.)

Despite the fact that Booster flirts here or there (more competently in Vol. 1 than he ever will again in his life), and is flirted with in turn, and despite the way he talks a good game, it doesn’t really seem like a game he’s all that invested in winning. In Vol. 1, he seems to be far more interested in adventure, fame, money and proving his mettle as a hero than in anything one might classify as romance.

One of the reasons why we bothered with the definitions above is to try on some words to perhaps explain what we see on-panel.

Despite an occasional reputation as a playboy, Booster’s only prospects throughout the whole of his first book are: Monica Lake, Trixie Collins, some woman named Staci we see once and never again, and some woman he basically flirts with solely to get under Lex Luthor’s skin, likewise put on a bus after a single brief appearance. Of those, Monica was obviously never meant to be Booster’s love interest: He clearly can’t stand her, and the feeling is shown to be wholly mutual. And as to poor Staci and the woman he ‘stole’ off of Luthor, they were — at best — one-night stands.

That only leaves Trixie, who seems to be clearly set up to be Booster’s love interest in a long-game— except for the part where the attraction looks decidedly one-sided.

To get more in depth (and therefore into why Booster looks more and more queer, especially when looking back in retrospect), we’ll go through these one by one.

Monica Lake

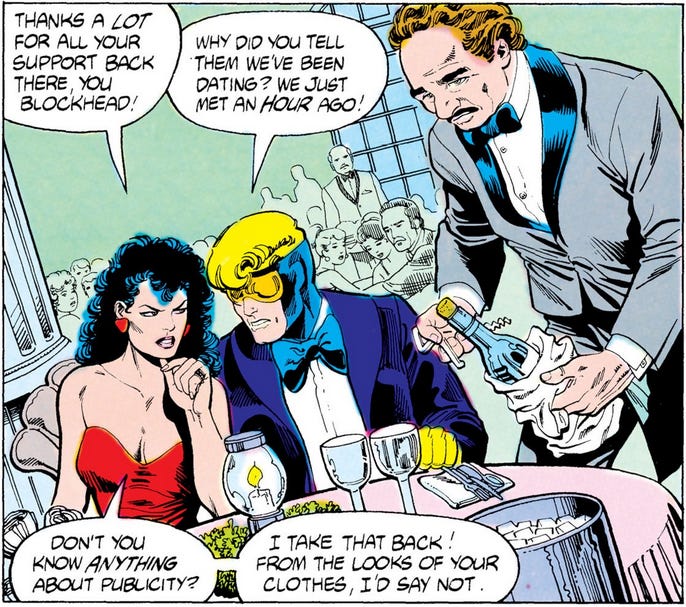

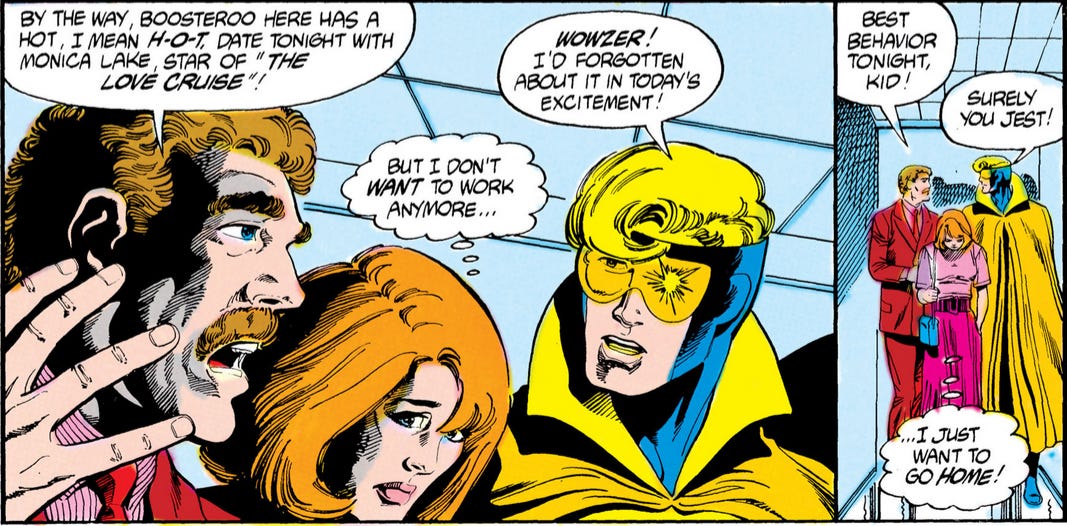

The first of these, actress Monica Lake, is introduced to us in Issue 3. Before that, we’re given no real sign that Booster has had, is looking for, or even wants a romantic partner (of any gender or lack of); he indulges in some braggadocio in flashback in a later issue57, as we’ve already discovered is a habit of his, but it’s easy to take as given from all available evidence that Monica is his first date in the 20th Century, one that was set up to be very public and glamorous, rather than anything more organic.

And instead of what one might assume would be the reaction of a young, allegedly-heterosexual, hot-blooded guy to the reminder of his impending date with Ms. Lake — maybe anticipation, excitement, or nervousness — Booster completely forgot that he had the date with an attractive female actress to begin with.

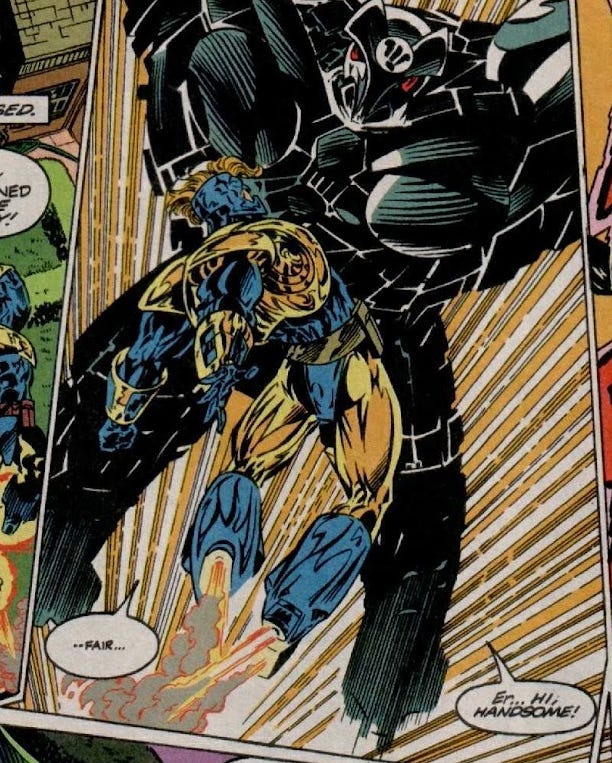

Despite what is clearly a joke here, though, Booster really isn’t on his best behavior, though from a very different angle than implied: Essentially from minute one of this date, he obviously and openly dislikes Monica and isn’t the least bit subtle about it.

My own theory, posited here on Boldly Reading in my review of this issue58 is that Booster, before he even arrived at the restaurant, already planned on bombing this date. The evidence being that he dressed in a manner that is — to put not too fine a point on it — atrocious, despite the fact he’d been around long enough to pick up on what would at least be considered serviceable civilian attire, and that it takes him no time whatsoever to start matching Monica tit-for-tat in taking on a scathing tone.

Lending further credence to this theory — that Booster deliberately bombs this date — is the fact that just last issue59, Booster and Dirk Davis were butting heads and Dirk explicitly says that he (not Booster) is the one who decides what Booster wears and who he dates. Beyond the discomfiture of an older man attempting to exert that distressing level of control over a younger one, it gives a very clear reason why Booster would go out of his way to poison this well, perhaps intentionally dressing to horrify both Dirk and his date, and certainly coming into it with his claws out.

Just as intriguing here is Booster’s complaint that they only met an hour ago. First, because if he was anything of a real pickup artist or playboy, the short duration of time wouldn’t matter for the ultimate goal, which would be some kind of sexual gratification. You don’t necessarily need to like someone in order to have sex with them. Even if that wasn’t his end-game, it’s still demonstrated that Booster genuinely does know about publicity — in fact, he’s managed to leverage it into a fortune by this point — which is yet another point in favor of the theory that he came into this date looking to bomb it spectacularly, rather than with the intention of getting laid or testing the waters.

Second, the mention of it only being an hour since they met could also be a point in favor to Booster maybe being a couple of those terms defined above: demiromantic and demisexual, his interest in a partner more down to time and emotional connection than any initial attraction.

There’s plenty of evidence throughout the entirety of his existence that Booster might just be those particular variations of queer, especially later on. While he occasionally mentions off-panel love interests, we never actually see them. What exceedingly few times we do see him with female company he’s purportedly romantically interested in — which is relegated to one disastrous date and a couple of one-night stands in the 1986 series, then nothing at all until 1998 with Lorraine Reilly — half of them are openly performative and the other half could easily be read as being performative.

More often, though, when it comes to Booster being depicted in the romantically or sexually charged company of women— it’s outright and undeniable sexual harassment of Booster.606162

And we’ve already established just how easily and quickly Booster lies, particularly in self-defense, which is such a known closeting behavior that it’s hard to argue against it being exactly that. That makes the occasional never-seen off-panel love interest he mentions in the 2007 series the equivalent of, “I’ve had lots of girlfriends! —but no, you can’t meet them. Ever. Because they, uh— they’re very shy. It’s against their religions. They’re moving out of state. Yes, all of them. Right now.”

Cue furtive darting side-eye and a quick crab walk for the exit.

The biggest evidence for this being incredibly queer behavior on Booster’s part is right out in the open: Monica Lake is the first and last actual romantic date we see Booster Gold on— well, ever. He never actually goes out on a romantic date with anyone again, on-panel. He’s leaving some kind of event with Staci, he’s trolling Lex Luthor on Lex’s yacht, but in terms of a depicted date on-panel, this is it.

The last time we see Monica is to remind everyone how unlikable she is and to again contrast her to pure, virtuous Trixie, but for now, let’s move on to Staci and the woman Booster ‘stole’ off of Lex Luthor.

Here in Town, One Night Only

The next woman we see with Booster in any romantic context — aside some incidental flirting — is Staci.63 Like most women depicted in this book, her entire personality is one single trait, in this case ‘airheaded arm candy’, which says considerably more about Jurgens than it does about her or Booster. The spelling of her name is no doubt a deliberate choice on Dan’s part to impart what kind of woman she is. She does have the distinction of being one of the exceptionally few women to get an on-panel, on-the-mouth kiss off of Booster, though; at the time, it’s unlikely anyone could have guessed that, after this book ended in 1988, it wouldn’t be until after the very universe was rebooted in 2011 before anyone would get another.

Just for the sake of reference, this is the entire list:

If Booster didn’t already look queer for his complete lack of dating and romance between 1988 and 1998, the fact you can count all of his on-panel romantic kisses — ever — on a single hand is truly extraordinary evidence for it. If one wanted an interesting statistical fact that places that in context: He’s been stabbed by Harley Quinn more times (3)68 than he’s shared a kiss with a single woman (2, Godiva, see above).

Returning to Staci, she’s not really in the story long enough to get a feel for her except as a vehicle to show that Booster lives a glamorous, ostensibly sexually active, hetero life. In light of the above facts, though, it greatly strains credibility in retrospect.

The other woman69 — unnamed — is simply another story vehicle, present for exactly one page for Booster to demonstrate his suave superiority over Lex Luthor, never to be seen again after. Much like the others, her entire personality seems to be ‘airheaded arm candy’.

This brings us to the last person, and the only one to be given something of a personality and presence beyond just ‘bad sexist stereotype’.

Theresa “Trixie” Collins

More than any other character in Vol. 1, Trixie is perhaps the sharpest look into what young Dan Jurgens found laudable, desirable and emotionally appealing. What he considered to be a ‘good woman’. While we’re going to go into this in considerably more depth when we step over to the Doylist side of the line more fully, it’s something you can’t really detangle Trixie from entirely. Dan’s inability to write women in non-sexist ways is still on display with her, but in a much more subtle and insidious sense.

Despite that, however, Trixie does have facets and a personality, and is the only one Dan takes some time to flesh out as a character, even if she still reads as more of his ideal of a woman than as a real live woman, with her own inner world.

Returning to the in-universe perspective, Trixie’s interest in Booster is set up immediately; when it appears he’s involved with Monica Lake, her jealousy and possessiveness are right out front on panel70, a theme which evolves later into her acting as something of a scold throughout the rest of the book. Even a strange diversion into her appearing to get involved with openly sexist Dirk Davis doesn’t really change the fact of the strange emotional dance she attempts to engage Booster in.

Some of the earliest things established about Trixie are largely based on connotations71.

The denotation of a word is its literal definition; the one you find in a dictionary. The connotation, however, refers to the suggested meaning, including associations and emotional implications.

In this sense, connotations are a kind of literary shorthand. We’re to infer specific things: From the fact she’s from Kansas72 (that she’s wholesome and not at all trashy like these other women), to the way she dresses in long skirts (double-plus wholesome), to the fact she exercises and does not give into the temptation of a hot fudge sundae (because all good women want to have nice legs they don’t dare show off and don’t want to be fat cows)73, to the cross hanging on her aunt’s wall (which basically speaks for itself)74.

That’s not to say that she has no personality beyond those connotations. To the contrary, she’s one of the only people who seems to care about Booster as something other than a means to her own ends; she’s one of the few people to notice and point out just how much Booster is masking75.

She also wonders if he’s happy, notes that he seems lonely and otherwise seems to have a genuine interest in his well-being. In fact, if she had been allowed to develop as a character in a natural direction, unfettered from one-sided romantic longing and her creator’s staid brand of Midwestern sexism, she could have become both a solid, enduring character and a pretty powerful force in Booster’s life: Namely, as a genuine friend he badly needed at the time.

Given this section isn’t about Trixie or her failings as a narrative device, though, let’s get into why she doesn’t exactly manage to make Booster look less queer.

Despite what is fairly obvious interest on Trixie’s part, Booster seems oblivious. He’ll compliment her (much as he does Thorn76) almost casually, with no real sign it’s intended to be flirtatious. We do see Booster flirt in Vol. 1 — with an older woman he startles (in a playful fashion) in Issue 8, with the hostess at the hotel he checks into in flashback likewise in Issue 8, with the woman he steals off of Luthor, with Staci — and the difference between Booster flirting and Booster offering a frank, honest compliment is incredibly obvious.

For a few examples:

Notably, in the first one — even though it’s clearly flirtation — it’s also transactional on Booster’s part. He’s flirting with the intention of getting something out of it, in this case a hotel room without a reservation, which casts at least some suspicion on how sincere you can take such flirting to be. (Though even with the transactional nature of it, his compliment seems sincere and not the least bit facetious.)

The second one, referring to Thorn, is a plain-spoken compliment; there’s no hint that there’s any desire Booster’s attached to said compliment. And Trixie in the Goldstar outfit in the third is also just seemingly a casual compliment, if a goofy one; he doesn’t spend any time before or after really ogling her, which you might expect the reaction to be if there was any attraction present on his part.

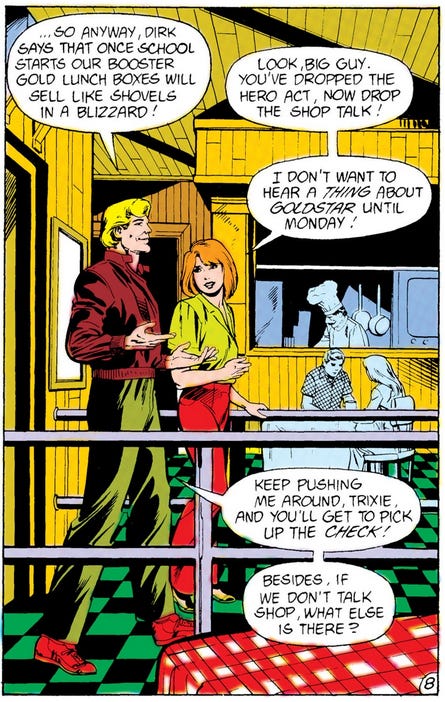

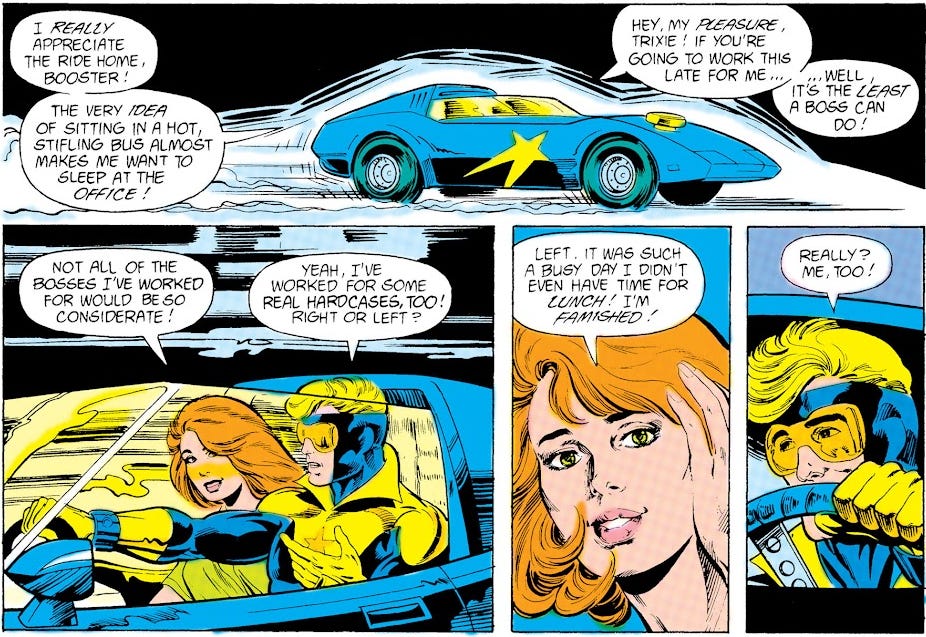

When we get into the decidedly one-sided attraction, aside from some incidental and clear jealousy on Trixie’s part before, the best place to start is when Booster’s taking Trixie home from work and they mutually decide to go out to dinner77. Right from the jump, it’s portrayed as exactly what it says on the tin: Two people grabbing a bite to eat.

Trixie’s habit of being overbearing starts showing up here, though in a somewhat low-level manner: She understandably doesn’t want a spectacle and insists that Booster dress down in civilian-wear. Obligingly enough, he does, but rather than diving into anything personal, Booster’s conversation is essentially all work and he seems baffled that there might be anything else one might talk about when out on a date with a beautiful young woman.

Where her body language is decidedly flirtatious, Booster’s entire demeanor throughout this is basically good-natured indulgence. He does as she asks, and when she decides to start trying to prod answers out of him, he gives them, albeit not exactly quickly. It’s the first time he gives anyone his actual name, though it’s still only after she asks for it, rather than as something he offers unprompted.

It’s very debatable how that conversation might have continued had it not been interrupted by a building fire and a couple of giant robots. Booster seemed to be leading into telling her he was from the future, but as to which version of the story he might have told, there’s just no way to know: Booster’s status as a highly unreliable narrator makes it impossible to guess whether he would have given her the somewhat cold version Skeets gave Superman several issues ago, or whether he would have admitted to having grown up in a world of subsistence survival, or maybe some other framing entirely.

One thing’s certain as it’s something consistent from retelling to retelling: If he did tell her that tale, he would have carried the responsibility for essentially ruining his own life, even though we’ve already established just how dire and hopeless that entire situation was.

Despite Trixie’s white hot jealousy manifesting immediately after she stands on the ground watching the battle above like everyone else and cheering her crush on, furious to the point where she storms off because Booster’s schmoozing the reporters by playing with the narrative about him and Monica Lake — proving he really does know publicity, thereby lending further credence yet to him intentionally bombing that first date — Booster not only doesn’t follow her, he remains completely unaware that she was kidnapped for two days in-universe78. Further, he doesn’t seem to think to question why she stormed off in the first place, or to even be aware that she had, which is not the behavior anyone would expect of even a very young man towards a romantic prospect.

Everything about how Booster acts and reacts towards Trixie seems platonic all the way up to the last part of the last issue of Vol. 1, enough so that even the tabletop game module All That Glitters79 mentions the seemingly futile one-sidedness of it on page 6:

Trixie would like herself and Booster to be making more serious decisions together, but she does not figure into Booster’s romantic life as she would like.

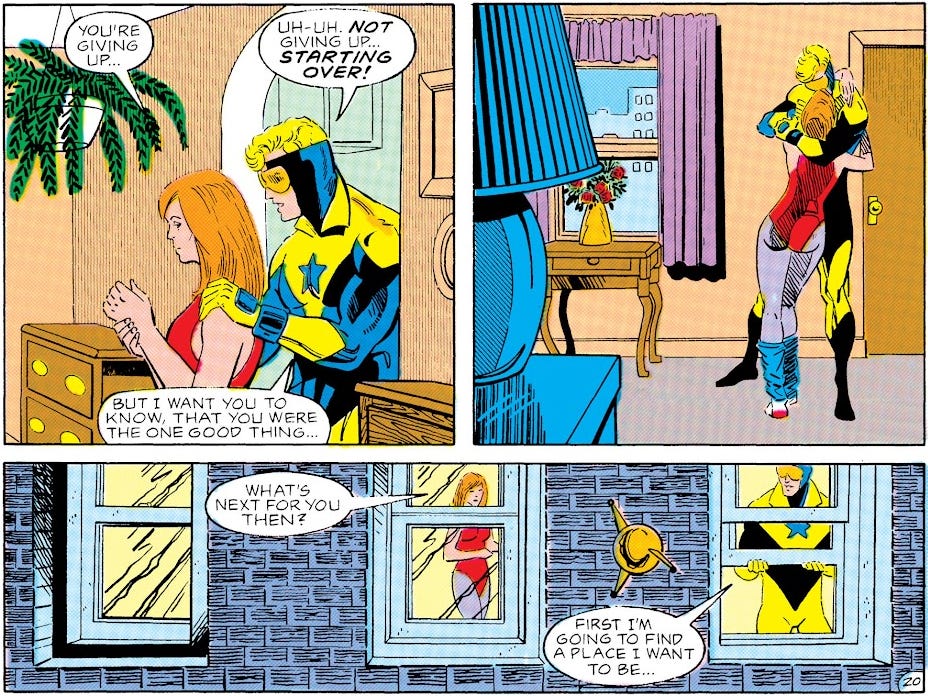

It’s only at the very end of Vol. 1, after an entire book where Trixie has been firmly friend-zoned by Booster, that she gets what seems to be anything back for her romantic devotion to him, in the form of a sincere compliment and a kiss80.

But even then, on Booster’s side, it seems more a consolation prize, or maybe a show of gratitude; he passes out of her life just like that. It’ll be twenty-four years before he kisses another woman on panel.

From there, Booster flies off to live with the Justice League and he doesn’t look back.

This is the last the two of them see of each other in the 20th century, if we don’t count the inconsistent cameo in the limited series Chase81, where Dirk Davis has not gone full villain and where Trixie and Booster are entirely frosty towards each other. It won’t be until 2021 when they meet again, after one hard universal reboot and one soft one, New52 and Rebirth respectively.82 Trixie (now Terri) seems like she’s grown out of her possessiveness, though like before, she also seems to be open to the possibility of a romance rekindling between them.

But just like before, despite Jurgens implying Terri is actually Rip Hunter’s mother83, Booster shows precisely no discernible romantic interest in her back; if their single kiss is still considered canon, then he makes no reference to it and indeed seems to still see her as only a friend and nothing more.

And — just like in 1988 — after the end of Blue & Gold, we don’t see her again.

And Booster still doesn’t look back.

Looking Back and Looking Forward

If you read Vol. 1 in isolation and never pick up another book with him, you could probably swerve around reading Booster as being a distinctly queer character who can (and does) resonate with a distinctly queer audience. Despite there being a great deal contained within Vol. 1 that allows him to appeal to a queer audience, compulsory heterosexuality84 is, as one might say, a hell of a drug.

Still, there’s no evidence even there that he is exclusively heterosexual, which means there’s also no evidence whatsoever that he isn’t queer in some fashion. It’s in Vol. 1, in fact, that you get the closest to anything like a solid confirmation of Booster’s alleged heterosexuality— and even then, it falls short. And after all the years that follow, just how short becomes incredibly apparent in retrospect.

The single only viable romantic prospect Booster has in Vol. 1 is firmly platonic on his side for 99.6% of it (and the remaining .4% looks like a participation trophy for Trixie for the two minutes it lasts). His unreliable narration makes even his braggadocio instantly suspect; not only about women, but about everything. He talks a far better romantic game than he ultimately plays.

But what is provable is that Booster’s backstory is filled with a number of different kinds of trauma — from witnessing domestic violence, to growing up in abject poverty, to having no resources he could turn to when in trouble, to being used (and ultimately discarded) by far more powerful forces — and all of them explain, if not excuse, why he would not only bolt into the past, but then also why he might just take a look at the geopolitical landscape of his newly adopted time and immediately straight-wash himself right into a closet.

He’s a survivor first, after all. Then again, a lot of queer kids are: they — we — have to be.

No one else is going to save us, so we have to try to save ourselves.

As stated at the start of this chapter, Booster’s first book looks a hell of a lot more queer in retrospect. Within Vol. 1 are enough elements of queer behavior to keep the dog on the scent trail, but it’s when you’re looking back at it from across the nearly four decades he’s been published that the hounds start baying.

Part of this is because he’ll spent the next ten years without so much as a date, and that he doesn’t seem to actually miss that. Part of it’s because the first and only genuinely authentic and emotionally intimate relationship we ever see Booster have with another human being is with another man; in fact, that will hold true from Justice League International to today (August 20th, 2025 just for serendipity’s sake), and with the same man across all of those years, no less. He successfully keeps everyone else at some greater or lesser — but always notable — distance, whether he intends to or not.

In Chapter 2, we’re going to look at what some of the influences our world might have been on this fictional one, and some of those real world things that contribute to reading Booster as queer, both in the sense of seeing him as such, but also in being a queer reader: Namely, the AIDS epidemic, gay-bashing, 80s sexism, probably some Reaganomics and what growing up in a small town in the upper Midwest might contribute to an author’s writing, for good and ill both. Among other things.

I hope I’ve got the gears turning. Sir Arthur and I will see you on the other side.

Obligatory Disclaimer: Yes, I wrote all of this for fun. I’m a writer, that’s something we do, and when it’s on a subject we love, it’s shockingly easy to end up with over 12000 words of queer literary analysis of a comic character (so far). I started it sometime in late May. I did my best to cross my t’s, dot my i’s and cite my sources. If you want to tell me what you think, please do feel free to either comment here or email, or find me on whatever social media platform.

Fanlore - Watsonian vs. Doylist, https://fanlore.org/wiki/Watsonian_vs._Doylist (as of June 19th, 2025, at 20:18 GMT)

Wikipedia - Death of the Author, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Death_of_the_Author (as of June 19th, 2025, at 20:52 GMT)

Boldly Reading - Booster Gold (1986) #3: A Hopefully Quick Sociological Digression, https://boldlyreading.substack.com/i/158410009/a-hopefully-quick-sociological-digression, SLWalker, March 2025

DC Comics - Action Comics (2016) #995, Dan Jurgens, March 2018

Ibid.

DC Comics - Booster Gold (1986) #13, Dan Jurgens, February 1987

DC Comics - Justice League Quarterly (1990) #10, Mark Waid, Spring 1993

DC Comics - Time Masters (1990) #1, Lewis Shiner, Bob Wayne, February 1990

DC Comics - Booster Gold (1986) #18, Dan Jurgens, July 1987

Washington and Lee Journal of Civil Rights and Social Justice Vol. 28, Iss. 1 - Blood, Sweat, Tears: A Re-Examination of the Exploitation of College Athletes, https://scholarlycommons.law.wlu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1531&context=crsj, Keely Grey Fresh, Winter 2022

The American journal of sports medicine - Epidemiology of concussion in collegiate and high school football players https://doi.org/10.1177/03635465000280050401, Guskiewicz, K. M., Weaver, N. L., Padua, D. A., & Garrett, W. E., Jr, 2000

DC Comics - Secret Origins (1986) #35.1, Dan Jurgens, January 1989

Journal of Issues in Intercollegiate Athletics, Vol. 7, Iss. 1, Art. 14, Pg. 166 - NCAA Division-I Athletic Departments: 21st Century Athletic Company Towns, https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1139&context=jiia, Richard M. Southall, Jonathan D. Weiler, January 2014

Secret Origins #35.1

DC Comics - Justice League: Generation Lost (2010) #5, Judd Winick, Keith Giffen, September 2010

DC Comics - Booster Gold (1986) #14, Dan Jurgens, March 1987

Proceeding of the Royal Society B, Vol. 292, Iss. 2040 - Poverty is associated with both risk avoidance and risk taking: empirical evidence for the desperation threshold model from the UK and France https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/10.1098/rspb.2024.2071, Benoît de Courson, Willem E. Frankenhuis and Daniel Nettle, February 2025

Surviving the Streets of New York - Experiences of LGBTQ Youth, YMSM, and YWSW Engaged in Survival Sex https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/42186/2000119-Surviving-the-Streets-of-New-York.pdf, Meredith Dank, Jennifer Yahner, Kuniko Madden, Isela Bañuelos, Lilly Yu, Andrea Ritchie, Mitchyll Mora, Brendan Conner, February 2015

Wikipedia - Unreliable Narrator, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Unreliable_narrator (as of August 12th at 23:47 GMT)

DC Comics - Booster Gold (1986) #5, Dan Jurgens, June 1986

Wikipedia - Masking (behavior), https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Masking_(behavior) (as of July 24th, 2025, at 14:46 GMT)

Secret Origins #35.1

DC Comics - Justice League Quarterly #7: Klaarsh Reunion, Michael Jan Friedman, Summer 1992

DC Comics - Booster Gold (2007) #33, Keith Giffen, J.M. DeMatteis, August 2010

Booster Gold (1986) #13

Secret Origins #35.1

Justice League Quarterly #10

DC Comics - Booster Gold (1986) #13, Dan Jurgens, February 1987

DC Comics - Booster Gold (1986) #22, Dan Jurgens, November 1987

Booster Gold (1986) #5

DC Comics - New Teen Titans (1980) #37, Marv Wolfman, December 1983

DC Comics - Booster Gold (1986) #20, Dan Jurgens, August 1987

DC Comics - Booster Gold (2007) #31, Dan Jurgens, June 2010

DC Comics - Extreme Justice #12, Robert Washington III, January 1996

DC Comics - Justice League America #70, Dan Jurgens, January 1993

DC Comics - Superman #74, Dan Jurgens, December 1992

DC Comics - Countdown to Infinite Crisis, Geoff Johns, Greg Rucka, Judd Winick, May 2005

DC Comics - The OMAC Project #1, Greg Rucka, June 2005

DC Comics - The OMAC Project #6, Greg Rucka, November 2005

DC Comics - Booster Gold (2007) #5, Geoff Johns, Jeff Katz, February 2008

DC Comics - Justice League: Generation Lost #1, Judd Winick, Keith Giffen, July 2010

DC Comics - Booster Gold (1986) #3, Dan Jurgens, April 1986

DC Comics - Booster Gold (1986) #4, Dan Jurgens, May 1986

Wikipedia - He never married, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/He_never_married, (as of July 28th, 2025 at 18:55 GMT)

Wikipedia - Sexual attraction, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sexual_attraction, (as of July 28th, 2025 at 21:45 GMT)

Wikipedia - Queerplatonic relationship, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Queerplatonic_relationship, (as of July 31st at 19:33 GMT)

Wikipedia - Kinsey Scale, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kinsey_scale, (as of July 28th, 2025 at 21:45 GMT)

DC Comics - Chase #4, Dan Curtis Johnson, May 1998

DC Comics - Chase #6, Dan Curtis Johnson, July 1998

DC Comics - Formerly Known as the Justice League, Keith Giffen, J.M. DeMatteis, September 2003

Booster Gold (2007) #31

SUPER-BUDDIES: Giffen/DeMatteis on Blue Beetle and Booster Gold, via WayBack - https://web.archive.org/web/20141129172654/http://www.comicosity.com/super-buddies-giffendematteis-on-blue-beetle-and-booster-gold/#expand, Matt Santori-Griffith, November 2014

Sexual Behavior in the Human Male, Chapter 21: Homosexual Outlet: Bisexuality, Pg. 656 - https://www.ipce.info/booksreborn/Kinsey%20Book%20Sexual%20behavior%20in%20the%20human%20male.pdf Alfred Kinsey, Wardel Pomeroy, Clyde Martin, 1948

Wikipedia - Kinsey Reports https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kinsey_Reports (as of July 28th, 2025 at 22:05 GMT)

DC Comics - Extreme Justice #1, Dan Vado, February 1995

DC Comics - Booster Gold (1986) #8, Dan Jurgens, September 1986

Boldly Reading: Booster Gold (1986) #3

DC Comics - Booster Gold (1986) #2, Dan Jurgens, March 1986

DC Comics - Booster Gold (2007) #33, Keith Giffen, J.M. DeMatteis, July 2010

DC Comics - Booster Gold (2007) #37, Keith Giffen, J.M. DeMatteis, December 2010

DC Comics - Justice League International (2010) #2, Dan Jurgens, December 2011

Booster Gold (1986) #18

DC Comics - Booster Gold (1986) #25, Dan Jurgens, February 1988

DC Comics - Justice League International (2011) #11, Dan Jurgens, October 2012

DC Comics - Justice League International (2001) Annual #1, Geoff Johns, October 2012

DC Comics - Harley Quinn (2016) #74, Sam Humphries, September 2020

DC Comics - Heroes in Crisis #1, Tom King, September 2018

DC Comics - Booster Gold #23, Dan Jurgens, December 1987

Booster Gold (1986) #3

Gotham Writers - Writer’s Toolbox, https://www.writingclasses.com/toolbox/ask-writer/why-is-connotation-important-in-fiction, Brandi Reissenweber

DC Comics - Booster Gold (1986) #1, Dan Jurgens, February 1986

Booster Gold (1986) #5

Booster Gold (1986) #3

Booster Gold (1986) #4

Ibid.

DC Comics - Booster Gold (1986) #10, Dan Jurgens, November 1986

DC Comics - Booster Gold (1986) #11, Dan Jurgens, December 1986

Mayfair Games Inc. - DC Heroes RPG: Booster Gold: All That Glitters, Greg Gorden, 1987

DC Comics - Booster Gold (1986) #25, Dan Jurgens, February 1988

Chase #4

DC Comics - Blue & Gold #1, Dan Jurgens, September 2021

DC Comics - Blue & Gold #6, Dan Jurgens, April 2022

Wikipedia - Compulsory heterosexuality https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Compulsory_heterosexuality (as of August 18th, 2025 at 23:03 GMT)

I finally finished reading! A delightful piece and I am anxiously awaiting the next chapter!

Super excited to read this later - I was telling a friend I missed character/ship manifestos hahahahhaa